Learning from the past, looking to the future

Former Raising Special Kids Executive Director Joyce Millard Hoie remembers a time from her childhood before the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) became law in 1975. As she and the other neighborhood children left for school, one boy with disabilities stood alone on the street corner watching them. At the time, no laws existed to give him—or other students with disabilities—the right to attend school with peers.

Mary Slaughter, Raising Special Kids’ first executive director, came to Arizona in the 1970s soon after The Arc of Arizona sued the state because of poor living conditions for disabled residents at the state institution in Coolidge. Slaughter was part of a team dedicated to improving these conditions. This involved moving people from institutional care by developing home- and community-based services throughout Arizona—services that many individuals with disabilities still benefit from today—while also preventing the need for institutionalization in the future.

While these stories demonstrate how far the rights of individuals with disabilities have come in Arizona and elsewhere, there’s always work to be done. Parents can play an active role.

HOW PARENTS CAN GET INVOLVED

Parents of children with disabilities who want to get involved can advocate in different ways, including sharing their family stories.

“Storytelling means everything,” Millard Hoie said. “It gives people a glimpse of what it’s like to raise a child with special needs. Sharing the hopes, joys, fears and challenges is so compelling and can make a difference to a legislator.”

Slaughter also encourages parents to consider advocacy tasks that fit them. Different roles can be filled by different personality types.

Some people want to protest and hold signs on the street, while others want to speak up during meetings with legislators, work on policy development, and more.

“All types are needed,” Slaughter said, “and different personalities might be drawn to different roles.”

Other parents who have advocated at different levels shared their experiences and tips.

Raising Special Kids parent leader Dawn Bailey started as a family advisor in Arizona’s Office for Children with Special Health Care Needs at the Arizona Department of Health Services. Through that role, she serves as the incoming president of the board of directors for the Association of Maternal & Child Health Programs. She uses her personal experience as the parent of a daughter with complex medical needs to elevate the needs of this community—both in her work and legislatively at the federal level.

When parents have the opportunity to talk with legislators, it’s important to keep stories brief. You may have only 10 minutes or less, so make your story concise. Practice it and time yourself. Bailey also advises parents to be prepared because they might get cut off mid-story—such as when legislators get called in for a vote.

Plan for a short time, making your story and request for action as impactful as possible, but be prepared in case you receive more time. Someone else may step in, ask questions or want to hear more.

It’s also key to know your audience. Understand what resonates with them so you can craft your message in a way that aligns with their priorities. If you know their concerns are fiscal, share long-term financial effects. If certain services are lost, how will it affect the budget in the long run?

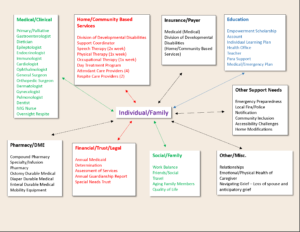

While it’s important to have a compelling story, visuals can also be effective. Bailey mentioned a care map she has shared, which outlines the different requirements in caring for her daughter.

“I can tell you with words how chaotic it is,” she said. “But let me show you how chaotic the systems are that I navigate daily to keep her world spinning.”

Sharing numbers and statistics can also drive points home. The National Survey of Children’s Health includes data on children with and without special health care needs. Initially, it can seem like only a small percentage of children are affected by certain decisions, Bailey noted, but providing data about the number of children impacted or the percentage of the population represented can help convey the issue’s significance.

“Bring data showing numbers or percentages,” she said. “The stories are impactful, but marry them with data.”

Parent leader Nicole Guysi has experience at the federal level through her involvement with national blindness groups and at the state level advocating against a bill related to guardianship. Her daughter has multiple medical diagnoses, and Guysi works for a public school district as a transition specialist lead.

Guysi and others opposed a bill that would have automatically placed all adults qualifying for services from the Division of Developmental Disabilities under guardianship.

At the time, this bill seemed to be moving quickly through the Legislature, Guysi said, possibly because it was proposed by a senator who is a parent of an individual with special needs.

“There was a perception that this bill couldn’t be questioned because they held the perspective of a parent of someone with disabilities,” Guysi said. “And I feel this individual came from a place of genuine concern, wanting to make things better for families.”

Several local parents and advocacy groups disagreed with the bill, which was ultimately stopped after meetings with family members and advocates who voiced their concerns. They focused on agreeing with the legislator that changes in Arizona’s guardianship process were needed but could be accomplished differently.

“Advocacy is effective when the end goal is to determine what’s best for the community—not serving one’s own agenda,” Guysi said. “If you go forward with the mindset of collecting information and collaborating, it helps you advocate more effectively. Advocating is really about bettering the community—not just your community, but the community as a whole.”

OTHER RESOURCES FOR PARENTS

While it can seem uncomfortable to write or speak to legislators about concerns, others encourage parents to get involved and learn as they go.

Online tools are available, including:

- Find My Legislator for Arizona: azleg.gov/findmylegislator

- The Arc’s templates for contacting national legislators: p2a.co/lRPDZ5C

Brandi Coon played an instrumental role in advocating for the 1115 waiver amendment that allowed parents in Arizona to become paid habilitation and attendant care providers for their children under age 18. This program became temporarily available to parents during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Coon and other parents saw a need to extend it. They joined together, advocating to make the program permanent to help address provider shortages and continuity of care. Coon’s son is medically complex.

“I think what makes advocacy like this successful is asking for meetings with the intent to ask questions and understand other perspectives beyond our agenda,” Coon said. “We met multiple times with AHCCCS leadership and were able to form a good working relationship. We came in with solutions and ideas, not complaints.”

AHCCCS, or the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, developed and submitted the proposal to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to establish this option and later made it permanent. During the process, families shared statistics related to reduced hospital visits since the program started.

More recently, Coon has been involved in advocacy related to proposed cuts to developmental disabilities and Medicaid services. She encourages parents who are unsure about speaking to legislators or writing letters to push past their fears.

“I might have been nervous to speak up, but the alternative was even worse,” she said, referring to possible changes to her son’s services and resources.

Guysi suggests that parents participate in advocacy classes whenever possible. Even if it’s a program they have attended before, they can learn from new individuals and fresh topics.

Coon also encourages parents to learn about the history of activism that led to IDEA and the Americans With Disabilities Act. As a younger parent now in her 30s, she said she grew up with no concept of institutionalization or school segregation.

“It’s important not to take these movements for granted,” she said. “All these rights that we are used to in this society today came about because somebody else before us asked for change. Now we’re picking up the torch.”

It’s important to not take these movements for granted. All these rights that we are used to in this society today came about because somebody else before us asked for change. Now we’re picking up the torch”

Raising Special Kids has more than 300 parent-leader volunteers. This leadership program provides opportunities for parents to develop their advocacy skills while serving others. More information is available at raisingspecialkids.org/get-involved/parent-leadership.

“Parent advocacy has always been a driving force behind progress in disability rights,” said Raising Special Kids Executive Director Christopher Tiffany. “The services and protections we have today exist because families before us spoke up and took action.”